CHAPTER VI. THE COMET: A Contribution by Paul Adam

WELL, it’s my turn. I don’t know why—they always seem to saddle me with tricky chapters, with a lot happening in them, and the thing is, of course, that I’m not a writer at all, really. Still, maybe that’s just as well—I can get on with things without bothering about descriptions and atmosphere and “style” and all that. The way I do it is to try to imagine I’m simply writing you a letter and telling you out straight. So here goes:

Dear Reader: I’d better start, I think, at the point when we were all stuck there in Scotland when Uncle Steve’s messages broke off.

You can imagine the excitement. We didn’t understand things in the slightest bit (it’s maybe just as well, in view of all that happened afterward); all we knew was that somehow we had to get back to Mars—Jacky and me, that is, and Mike, who was in America. And the only hope was to contact Dr. Kalkenbrenner, for we knew he’d been working on a rocket too, and it might be almost ready for the trip.

I can’t begin to tell you the tremendous amount of to-ing and fro-ing that went on. J.K.C. went into a kind of frenzy. He wrote letters and sent them whizzing across to America, and the place was thick with cablegrams and telegrams, and talk about the telephone!—I got to the stage when I was hearing it in my sleep. Calls to our mother and father, calls to travel agencies to book flight passages for all of us to go to the U.S.A., trans-Atlantic calls to Mike’s mother and father and Dr. Kalkenbrenner himself that must have cost a fortune.

And, of course, the pay-off was when J.K.C. did finally contact Dr. K., that he knew a great deal about it all already! For as you know, there was old Mike, in his usual way, spilling the beans and nosing in! We’d known he was in America, of course, but not that he’d actually reached Chicago and had looked up Dr. K. (he would!) and was right in the thick of it all.

Well, to cut a long story short, as they say in books (although this is a book, so I might as well say it), we got everything taped as far as we could in Scotland, and then we set off for the south—the whole crowd of us.

And in London we met our own mother and father, who had come up specially, and there were tremendous scenes in a big hotel.

“No, no,” said poor old Mum, “my children my poor children! etcetera—I can’t let them go all that dreadful distance again, and so on, oh dear, I shall worry terribly, I worry if they go off for an afternoon by the sea themselves. Oh dear, to think of them all the way up there on Mars, etcetera.”

“But what about Mr. MacFarlane?” says J.K.C.

“Yes, what about him?” I chime in myself, and Jacky doesn’t say very much at all, for although she wants to come, of course, there’s another part of her that doesn’t want to leave Mother either, and she’s almost in tears too. . . .

Anyway, talk, talk, talk, and in the end, with Father joining in on our side, it’s all agreed—although maybe not just quite as easily as perhaps I’ve made it seem: it was, in fact, a real fight to get permission.

“Only,” says Mother, “I do hope they are looked after this time. Miss Hogarth, do please promise that you will go too to look after them—they need the Woman’s Touch.”

And of course Katey was all for going—had been from the start; and she nodded; and then all three women (I mean Katey and Mother and Jacky) dissolved into floods of tears, floods and floods of them, and all us men went off to the lounge and had something to drink.

Now of course it’ll maybe seem crazy, but even though we’d been to Mars and through all those marvels, Jacky and I were really just as excited at the notion of flying to America! We’d never been, you see; and there was Mike, nearly two years younger than me, and he’d been—we could just picture him boasting and swaggering about the place thinking he’d put one over on us.

So wham!—off we go: zoom!

I wish I’d time to tell you all about this part of it—I mean the flight to America, and America itself. But it isn’t part of the story, really, so I’ll have to keep that for another time. Suffice it to say etc., etc. (as they put it in books), that we got there without any trouble—that is, the whole bunch of us except Mr. Mackellar, for he wasn’t coming. We had to leave him behind in England for he was all tied up with the airstrip job for the Government. The last we saw of him he was standing on the runway with Mum and Dad as we went out to the big American plane at Northolt, and he was positively stuffing himself with snuff, clouds and clouds of it, and offering some to Dad and Mum, and Dad was even absent-mindedly taking some and then sneezing like mad, but I think it was just a good excuse to pretend that that was why there was just a hint of tears in his eyes, and I don’t mind confessing (off the record) that I could have done with a small pinch of snuff myself for the same reason.

Ah well.

We got there—I mean America—and we met Dr. Kalkenbrenner, and there was Mike, beside him, strutting about like a young peacock! You’d think he’d invented Dr. Kalkenbrenner. (It’s an awfully long and queer name to write down every time, and I refuse to be as vulgar as Mike and call him “old Kalkers,” so I’ll simply say “Dr. K.” from now on and you’ll know who I mean. His other names were “Marius Berkeley,” so taking it all in all he was a bit of a mouthful—but a really decent chap all the same: about forty-five, and very tall and distinguished-looking, with a little pointed beard and a deep voice and a nice friendly smile. We took back all we had ever thought about him in the days when he wasn’t “on our side” after we came back from Mars last time. . . .)

As for the Comet . . . !

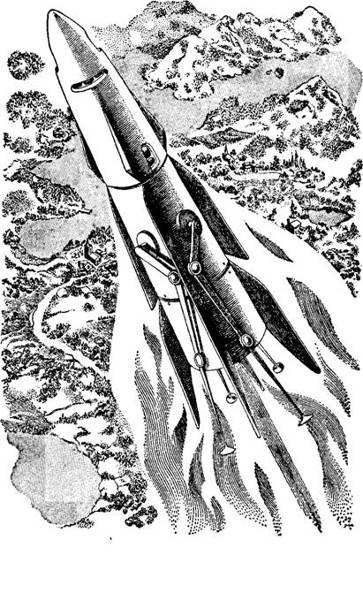

I’ve got to confess that fond as I was of the old Albatross, it really wasn’t a patch on Dr. K.’s job. Of course, it’s understandable enough—Dr. K. had had much longer to work on it than poor old Doctor Mac had had, and he had bags more money. There were what are called “Very Big Interests” behind Dr. K., and he had much of Doctor Mac’s research to build on and improve on. We know all that, and it doesn’t take away one whit of poor old Mac’s achievement, but the Comet really was something all the same. If you can picture the Albatross as, say, a good solid seagoing tramp, with just a bit of a homemade touch about it, then the Comet was almost a full-fledged liner.

To begin with, it was a different shape altogether from our old craft. The Albatross had a kind of bulbous nose, then tapered away to the tail—we used to say it was like a fish, and so it was, of course, but maybe it would be better to compare it to a kind of gigantic tadpole. The Comet wasn’t a bit like that: it was very long and slender, and went to a most delicate point at the nose end, then bulged out very slightly in the middle and went to another long slope- away at the back—like a cigar, really. In fact, it was much more like the usual idea of a rocket than the Albatross ever was, and with three huge fins, set like arrow feathers, which had enormous extending brackets, I suppose you could call them, which folded out when you weren’t in space, and made it possible for the whole affair to stand up on end on a kind of gigantic tripod.

That was the other thing, you see: the old Albatross had rested at an angle on a huge launching ramp, but the Comet stood right up on its tail, as it were—straight up into the air. On Earth, when we first saw it, it was held in a kind of framework of steel girders—a kind of scaffolding. But Dr. K. explained that that was only for additional strength—it was quite possible, because of the smaller gravity pull on Mars, for the Comet to take off from its own resting position on the tripod for the return journey. You see, the beauty of it all was that as you were approaching Mars (or anywhere else for that matter—the Moon or Venus or what have you), you could turn the whole rocket around in space and land on the surface very gently (braking like mad, of course, with the jets) tail first.

One other thing I ought to say (without being technical, for I don’t know enough—it’s only that I couldn’t help being kind of interested), and that is that the Comet used the idea, same as Doctor Mac had, of two separate fuels, but in a rather different way. In the Albatross, the two fuels were fired off through the same sets of tuyères, with one auxiliary set of tuyères to start off the second fuel, of course, once you were out a bit in space, but then everything going through the main set once the first fuel had cut off. In the Comet there were really two distinct rockets altogether. Fixed to the tail, on top of the Comet’s own jets, and underneath the tripod, was a huge “booster” rocket, as Dr. K. called it. This could be fired off by remote control from the spaceship’s cabin—and it was this that whipped up the colossal power to make the Comet rise from the ground—and even quite slowly, at first, again unlike the Albatross, which whizzed off zoom from the word go. Then, when you were well away from Earth’s surface, and the booster fuel had burned itself out, in one operation the whole contrivance fell away from the Comet’s tail and back down to Earth, and the Comet’s own jets came into action and there you were—on your way.

I should maybe add, lest you’re worrying about a great chunk of spent booster rocket coming wham out of the sky one day and biffing you on the head (R.I.P.), that as the spent booster fell away a special mechanism released a fairly sizable parachute, so that the whole thing floated down and there were no chances of serious accidents—at least you had time to see it, I mean, and could jolly well get out of the way pronto!

And the other thing was—just to complete the whole picture—that the Comet carried inside her all the component parts of a second booster, so that when you landed on Mars and were happily perched up on the tripod, the very first thing you did was fix this whole prefabricated contrivance onto the tail again, and there you were—all set for a take-off the moment you wanted to. And since it was Mars we were going to on this trip, and it had the smaller gravity pull, this booster didn’t have to be anything like as big and powerful as the one needed to shift us from Earth, so that was all right, and cut down on the weight the Comet had to carry.

So that’s that. (Phew! my hand’s all tired and cramped from writing all this—the trouble is that you get carried away and go on for longer than you first meant. Yd better stop now and pick up again later on. . . .)

Here we are, then—next day, and in fine fighting trim, all ready for another spell at the desk.

You know all about the Comet now—at least, maybe not all about it, but enough to be going on with: later on, Dr. K. will be publishing a book of his own going into all the real technical details. He’s also going to explain how it was that just about the time when we were due to set off, Mars was fortunately coming around toward one of its “nearest-to-earth” positions. We were jolly lucky in this, I must say—otherwise the journey would have taken much longer than the one in the old Albatross, even allowing for the improvements in the Comet. As it was, it still was a little longer, because of all kinds of complicated difficulties about the orbits of Earth and Mars being elliptic and not absolutely circular, and things like “aphelions” and “perihelions” nosing in to mess things up a bit. . . . Anyway, I don’t really know anything about all this, except that I’ve heard Dr. K. and the others talking about it and seen them working the whole business out with adding machines and such (and I looked up the words themselves in a scientific dictionary, so the spelling’s all right at least).

We had a hectic time getting ready. There were endless conferences and sessions with Dr. K., who had, of course, agreed wholeheartedly to the rescue expedition idea, once all the facts had been put before him, and was almost as excited as old J.K.C. himself, both by the thought of seeing his rocket in full blast and by the thought of going to Mars for the first time. For our part, we were desperately keen to get started for the sake of Uncle Steve and poor old Doctor Mac: it wasn’t as if we knew what was what up there in Mars, you know—we had simply no idea; except, of course, that something pretty serious was afoot, and that somehow we were the only ones who could do anything about it. Maybe it was even too late—we didn’t know that either: we just felt we had to get going.

And because we were all so eager, things were arranged in double-quick time. We had barely a week in Chicago before the whole business was cut and dried and we were ready to start. Dr. K.’s men had been working all around the clock on the last touches to the Comet—the place was such a den of activity as I’d never seen in my life before. Of course, because of the rush and turmoil, there were a hundred and one little improvisations—Dr. K. didn’t have time, for instance, to complete his own apparatus for feeding us on the journey (he’d worked out a real master plan for dealing with this side of things), so we had simply to make do again with Doctor Mac’s old “toothpaste” method—that is to say, normal food being impossible to handle in a spaceship because of the lack of weight, we had to feed from concentrates which were made up into paste form and packed into plastic tubes, just like toothpaste tubes, and you simply put the nozzle thing into your mouth and squeezed . . . ! Still, we didn’t mind this in the least: it was like old times for one thing, and for another it made us feel that Doctor Mac was somehow with us in spirit at least on this bigger job than his own old pioneering effort.

So everything was somehow arranged at last. For the last few days before the take-off we all moved out of Chicago altogether—went to live in the workmen’s huts miles out in the open country, close to where the rocket itself was.

I ought to say at this stage who exactly was going, I suppose.

Well, naturally, there was Dr. K.—that was an absolute must. And ourselves—another must, because of Uncle Steve’s last message, the whole reason for the voyage at all (I mean Jacky and Mike and Yours Truly, of course). Then there was Katey—Katey Hogarth; for our parents had made her promise to go, to look after us (as if it made a pennyworth of difference!). Dr. K. wasn’t very keen on the idea—quite charming and all that, full of old-world courtesy and such; but you could see that women in spaceships just wasn’t his idea of what was what—it wasn’t, as he put it, “a true feminine occupation, my dear.” But when Mike’s mother and father joined in, and said that they wanted Katey to go too, or they’d hold back on permission for Mike to go, well, there was nothing else for it, and Dr. K. had to give in.

We wanted one more. Dr. K. half considered taking one of his assistants; but most of them were married men, with vast families, and besides, if anything did happen to us in space, someone had to be about who could carry on Dr. K.’s research work back home in Chicago.

Of course, there was only one answer, and that was—

Archie Borrowdale!

He was exactly right—had all the technical qualifications because of his work with Mr. Mackellar, and so would be a great help to Dr. K. on the journey. And he was an expert shot, as it happened—he’d spent his student holidays in the Scottish Highlands after the stags, and was terrific with a gun; and you never knew, maybe the Vivores would have to be dealt with by guns—maybe they were different from the old Terrible Ones, which weren’t in the least affected by bullets.

And to crown all, of course, he was Katey’s fiancé, which was a bit of all right for her, and for him too, for he wouldn’t have liked her to go tearing off forty or fifty millions of miles away while he stayed biting his fingernails at home. Besides, we three—Jacky and Mike and me—we thought he was all right as well!

So there we were. In the last two days there was an odd sort of “slowing up” of things. We had lived at such a pace for so long that when everything was virtually over except the shouting we hardly knew what to do with ourselves.

Dr. K. had gone off somewhere or other to make some last-minute contacts and arrangements. All the work on the rocket had been done—the fuels were loaded, all the stores were packed aboard. We had plenty of food, of course, for we had to consider that Doctor Mac and Uncle Steve would be with us on the return journey—and besides, Dr. K. was a very careful man, and had loaded up plenty of additional supplies for “unforeseen emergencies,” as he put it.

So it only remained to wait for the moment of the set-off as it had been fixed according to certain weather conditions and other technical whatnots by Dr. K.—and that moment was still two days ahead (and at something like five o’clock in the morning—brrrr!).

So—we moped; we simply moped and moped. We were, in fact, nearly bored stiff—if you can believe that—on the very eve of setting off on a trip to Mars! Every now and again, of course, if we stopped to think of it, we’d get a queasy kind of falling-away feeling in the pits of our stomachs, like going down in an elevator suddenly; but for the most part we just didn’t think of it, somehow—there was a queer kind of numbness in us and even (in Jacky, I mean) a hint of tears. . . . Ah well! the way of the world, you know. Nothing ever does work out quite the way you think it will. . . .

What really saved the situation—kept us going in those last two strange days of suspense and waiting—was Miss Maggie Sherwood. Maybe I should say a word or two about her—Dr. K.’s niece, you know, as Mike has already mentioned.

She had come out to the launching site with us and was living in one of the huts, same as we were. She and Mike were as thick as thieves—they’d struck up a real friendship as soon as they had met in Chicago, and I must say they suited each other well. Maggie was about the same age as Mike, and her hair had a tinge of red in it (his was bright carrot). She was a big strong kind of girl, always leaping about—never still for a moment; tremendous fun, really—plenty of energy about her. Not very pretty—I can’t say that; but a nice sort of squashed-in face[2] that looked just swell when she smiled—and she was nearly always smiling.

Anyway, that was Maggie more or less, and as I say, she pulled us through those last two days. She was as lively as a cricket—always hatching up some scheme or other to amuse us. When she wasn’t in the thick like that she was off for hours on end with the bold Mike, the pair of them with their heads close together, and whispering, as if they were planning something. Once, I remember, they both were missing for several hours—nobody had any idea where they were. We searched everywhere—all over the camp; and it was Archie who spotted them at last, clambering stealthily down the long metal ladder that led up to the tiny entrance hatch in the side of the Comet.

When we asked Mike what the pair of them had been doing for so long in the rocket’s cabin, when it was strictly speaking out of bounds till we went into it on business as it were, he just shrugged.

“Oh, nothing. Just taking a last look around, you know—at least Maggie was. Don’t forget she mightn’t ever see it again—or her uncle either for that matter—or even any of us. You never know. We might blow up before we ever leave Earth at all—or we might be hit by a meteor in space—or there are always the Vivores when we do touch down on Mars, whatever they might be.”

“Cheerful, aren’t you,” sniffed Jacky (but there was just a little shake in her voice—for any of these things could easily happen to us on a job like this: it’s no simple trip to the seaside, shooting off to Mars, you know . . .).

But at last the time did pass, and it was the final night of all. Dr. K. had returned from his trip into Chicago and we all had a kind of solemn supper together before going to an early bed. Mike’s mother and father were there, of course, and J.K.C., and all of us who were going—us three and Katey and Archie. And—needless to say—the inevitable Maggie.

We’d meant to have speeches—some kind of celebration, almost; but you know, when the time came it just couldn’t be done—just couldn’t. Even Maggie was subdued; and for the first time, just before we all parted for bed, I saw that she wasn’t all just bounce and energy after all—there was a softer side.

She went close up to Dr. K., and her eyes were very wide and a little bit starry, the way Jacky’s always go when tears aren’t all that far away. And she whispered—perhaps I shouldn’t really have been listening, but I couldn’t help it, I was so close to Dr. K. myself.

“Berkeley,” said Maggie, very softly (it was the ridiculous name she always called him), “Berkeley, I wish you’d say right now that I could come with you tomorrow—I wish I could have your permission.”

He shook his head.

“You’re all I have in the world, Berkeley,” she went on, “and I’m all you have. We really ought to be together. There’s plenty of food in the rocket—and plenty of spare air from the breathing apparatus—and you’re well under the weight complement, even allowing for Mr. MacFarlane and Dr. McGillivray on the way back. . . . Won’t you say yes?”

“I can’t, my dear,” he answered, with a saddish kind of smile. And she shrugged.

“Oh well. I gave you the chance at least. In that case I guess I won’t be around tomorrow morning—you know I don’t like partings, even for a little time; I always hated railway stations. I’ll just stay out of sight somewhere. . . .”

She put her arms around his neck and kissed him. And his eyes were a bit starry too—in fact, all our eyes were when she came around us one by one and told us she wasn’t coming out in the morning.

“I’ll say my so-longs now,” she said, “and we’ll leave it at that. O.K.? Be seeing you. . . .”

And that was it. We all trooped to bed, feeling very subdued. I remember, after I’d undressed and put the lamp out, standing for a long, long time by the window of my bedroom, looking out to the tall slim shape of the Comet, almost a mile away. It gleamed a little in the moonlight—gleamed silver; like the strange far spire of some cathedral of the future, maybe, in a shadowy city all huddled in the drifting ground-mist which wreathed the tripod base.

I looked beyond—into the star-clustered sky. In a few hours we ourselves would be up there too—hurtling into the unknown—or, at least, to some of us, the partly known. Would we ever find Steve and Doctor Mac even if we did reach Mars? Would they be alive if we did find them? Would we ourselves ever return?

My gaze came back to Earth, attracted by a slight movement around the corner of one of the encampment huts. A small figure was moving stealthily forward in the direction of the rocket; and I recognized the unmistakable features, in a sudden glint of moonshine, of Maggie Sherwood.

I thought I understood her feelings. She, who was being left behind—left alone, separated from her friends, her only relative—was going out across the silent field for one last forlorn look at the great rearing structure of the Comet. Then, in the small hours, perhaps, she would creep back desolately to bed—would waken in the morning to the great explosive roar which would tell of our departure—would see the vast, silvery cigar shape rise slowly, spouting fire, gaining speed, more and more speed, until at the last, when it was no more than a tiny pencil against the pale blue of the morning sky, it would disappear suddenly in one last little spurt of drifting smoke . . . and she would cry a little, perhaps, and then leave the encampment for Chicago, to take up normal life in the boarding school there, as had been arranged.

I felt very sorry for her as I crept into bed; and so lay for a long time, just thinking and dreaming—and waiting; until, in spite of everything, I dozed off to sleep. . . . (I hope you’ll forgive this bit of “fine writing,” by the way, as J.K.C. calls it: I did feel it all rather strangely that night. Ah well.)

It was cold—terribly cold—when we drove next morning to the ship. We shivered, in spite of the warm clothing we wore. We assembled in the reinforced concrete hut close beside the base of the gigantic machine that was to be our only home for so many, many weeks.

We said our farewells—to Mike’s mother and father, to Dr. K.’s assistants, to dear old J.K.C., who was in a pale kind of awe at last, and silent for once, now that the moment of climax had come.

One by one we mounted the long swaying ladder and went through the little dark entrance hatch in the Comet’s gleaming side. We took our places—still in silence, following out the instructions that had been dinned into us at a dozen conferences.

Katey was very white—her lip trembled a little. I saw Jacky take her hand and squeeze it comfortingly—after all, she had been through it all before. . . .

Archie took up his position beside Dr. Kalkenbrenner at the control panel. The Doctor looked around inquiringly and we all nodded from the bunks in which we lay—to which, indeed, we were strapped, in readiness for the tremendous impact when the Comet’s own jets should come into use after the release of the booster.

Twisting my head around on the sorbo pillow, I could see J.K.C. and some half-dozen assistants on the ground, close to the door of the concrete hut. J.K.C. waved once, then he and the others trooped inside for shelter from the terrific blast there would be.

A long silence. I heard Dr. K. counting slowly to himself: “Seven—six—five—four—three—two—ZERO!”

And instantly there was an immense explosion, seeming almost to shatter our eardrums. Far beneath, the ground seemed to rock and tilt—then the concrete hut seemed to reel and steady itself—receded—grew smaller, smaller and smaller . . . and with the danger from the blast now gone, J.K.C. and the others—tiny, tiny black figures—rushed out once more, waving ecstatically after us as, in full triumph, the Comet rose higher and higher into the pale sky. . . .

the Comet rose higher and higher into the pale sky

The speed of our ascent increased—the figures, the hut itself—all were lost to view. Dr. Kalkenbrenner, by the instrument panel, cried out to us in warning as he prepared to release the booster and set the Comet’s own jets into action.

A second explosion—even more gigantic-seeming than the first. An immense hand seeming to press me down and down into the soft mattress . . . and everything swam before my eyes and went black. . . .

When I came back to consciousness—slowly at first—all was quiet. We were in full flight—were already many, many hundreds of miles away from Earth, heading toward the Angry Planet we knew so well—and yet so slightly too.

I looked around. Some of the others had already recovered also—others were still blacked out. In the confusion of the moment it was as if we were still in the dear old Albatross; and I remembered with a chuckle the bewilderment we had seen then on the faces of Doctor Mac and Uncle Steve when the door of the store cupboard had wavered open and we three stowaways had floated out to confront them.

I set to loosening the straps that held me, so that, for old times’ sake, I could sail off the bed in the old weightless way. As I twisted around to reach the buckle, my eyes fell on the metal door of one of the storage cupboards in the Comet’s cabin, not unlike the old storage cupboard on board the Albatross.

For an instant I thought I was dreaming—that I was still in a mist from the black-out and so had confused the two journeys.

But I was not dreaming! Not by a long chalk! The door of the Comet’s storage cupboard was wavering open—someone was floating out toward us, as we had floated on that other occasion!

I cursed myself for feeling so sentimental about Maggie Sherwood the evening before—for wasting all my good sympathy on her. I knew now why she had crept out from the encampment in the moonlight to steal toward the rocket!

She even had the nerve to wink at me now as she floated silently past my bunk and drifted on to give a patronizing flying kiss to an utterly bewildered Dr. Kalkenbrenner!

And Mike, the scoundrel, was winking too!